When engineers mention the “7 layers of the internet,” they are usually referring to the Open Systems Interconnection (OSI) model-a conceptual framework that defines how data moves between networked devices. But here’s a crucial detail: the OSI model was never meant to describe the actual architecture of the internet. Instead, it was designed as a teaching and troubleshooting tool. The real internet runs on a different system entirely.

Understanding this distinction matters. In an era where digital myths proliferate-from “Level 7” horror stories to exaggerated claims about hidden networks-grounding our knowledge in verified technical foundations is essential.

Origins and Purpose

The OSI model emerged in the late 1970s, a time when computer networks were fragmented. Companies like IBM and Digital Equipment Corporation used proprietary protocols (SNA, DECnet) that couldn’t talk to each other. To solve this, the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) published the OSI reference model in 1984. Its goal wasn’t to build a working network but to create a universal language for discussing how networks should function.

That language proved powerful. Even though the OSI model never became the internet’s operational backbone, it gave engineers, students, and technicians a shared mental map for diagnosing problems and designing systems.

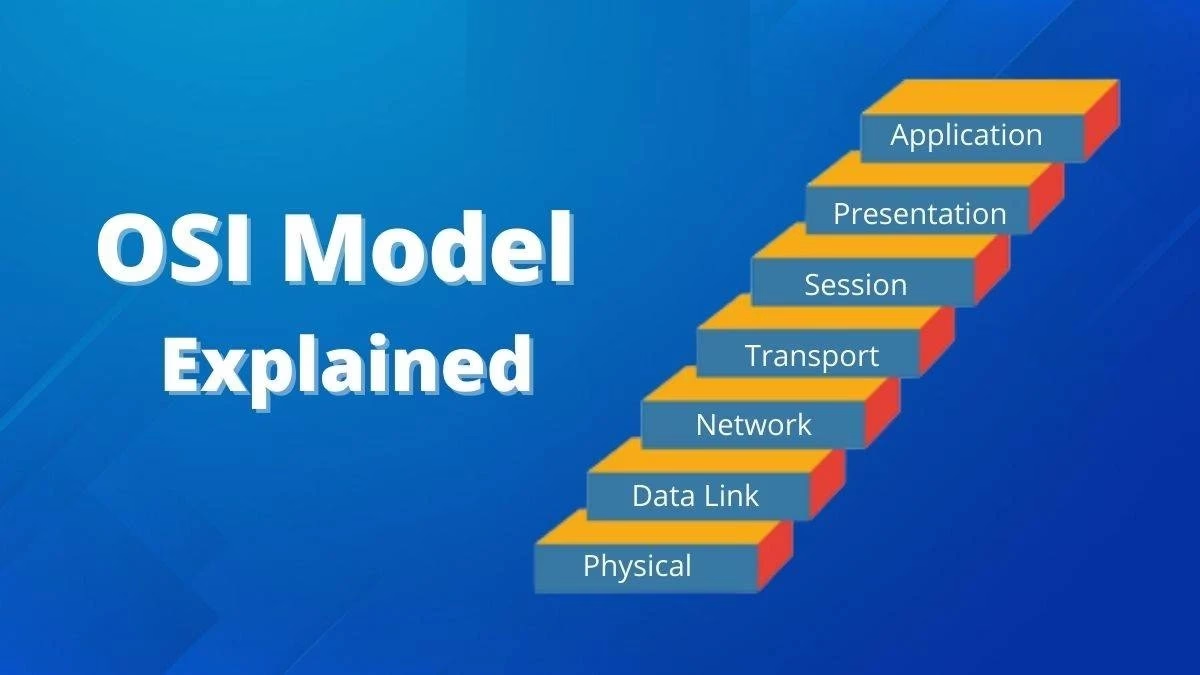

The Seven Layers, Explained Simply

The model breaks communication into seven layers, each handling a specific job. Data starts at the top on the sender’s side, moves down through the layers, travels over the network, and climbs back up on the receiver’s side.

- Physical Layer (Layer 1)

This is where bits become signals. Cables, fiber optics, Wi-Fi radiosall the physical hardware that carries raw data. It’s not about meaning; it’s about voltage, light pulses, or radio frequencies. - Data Link Layer (Layer 2)

Responsible for reliable transmission between two devices on the same local network. It uses MAC addresses to deliver frames of data and detects basic errors. Think of it as the neighborhood courier who knows every house on the block. - Network Layer (Layer 3)

This is the routing layer. It uses IP addresses to decide how packets move from one network to another across the globe. Routers operate here, making split-second decisions about the fastest path. - Transport Layer (Layer 4)

Ensures data arrives completely and in order. TCP (Transmission Control Protocol) guarantees delivery and retransmits lost packets; UDP (User Datagram Protocol) prioritizes speed over reliability—ideal for video calls or live streams. - Session Layer (Layer 5)

Manages conversations between applications. It opens, maintains, and closes sessions. If your Zoom call drops and reconnects seamlessly, this layer played a role. - Presentation Layer (Layer 6)

Translates data into a format the application can understand. It handles encryption (like TLS), compression, and character encoding—ensuring that a file sent from a Windows machine displays correctly on a Mac. - Application Layer (Layer 7)

The only layer users directly interact with. Protocols like HTTP (web), SMTP (email), and FTP (file transfer) live here. Importantly, this layer provides services to applications—it is not the browser or email client itself.

OSI vs. TCP/IP: What Actually Powers the Internet

Despite its fame, the OSI model is not what runs the internet. That honor belongs to the TCP/IP model, developed in the 1970s by Vinton Cerf and Robert Kahn for the U.S. Department of Defense’s ARPANET. TCP/IP is leaner—just four layers—and built for real-world use, not theoretical purity.

In practice:

- TCP/IP’s Application Layer covers OSI Layers 5, 6, and 7.

- Its Internet Layer matches OSI Layer 3.

- Transport Layer is nearly identical.

- The Link Layer combines OSI Layers 1 and 2.

The internet succeeded because it prioritized functionality over elegance. As computer scientist Andrew Tanenbaum once noted, “The OSI model is a beautiful theory killed by a ugly fact: the internet already worked.”

Today, the OSI model survives not in routers or servers, but in classrooms and IT certification exams. Network administrators still use its layers to troubleshoot: “Is this a Layer 1 cable issue or a Layer 7 app bug?” It’s a diagnostic lens—not an engineering blueprint.

Why This Confusion Persists

Pop culture often conflates the OSI’s technical layers with fictional “levels of the internet” (e.g., dark web hierarchies). But this is a fundamental error. The OSI describes how data moves, not what content exists. A Layer 7 application could be a public news site or a private medical database—both operate at the same logical level.

Misunderstanding this leads to myths: that “going deeper” into the internet means accessing more dangerous or secret content. In reality, accessibility depends on authentication, encryption, and policy—not network layers.

Conclusion

The OSI model is a map of process, not place. It clarifies communication mechanics but says nothing about the internet’s content landscape. Separating this technical truth from digital folklore is the first step toward informed digital literacy.

The next article in this series will leave theory behind and examine the real divisions of online content: the surface web, the deep web, and the dark web—what they are, how big they really are, and why most of what you’ve heard is wrong.