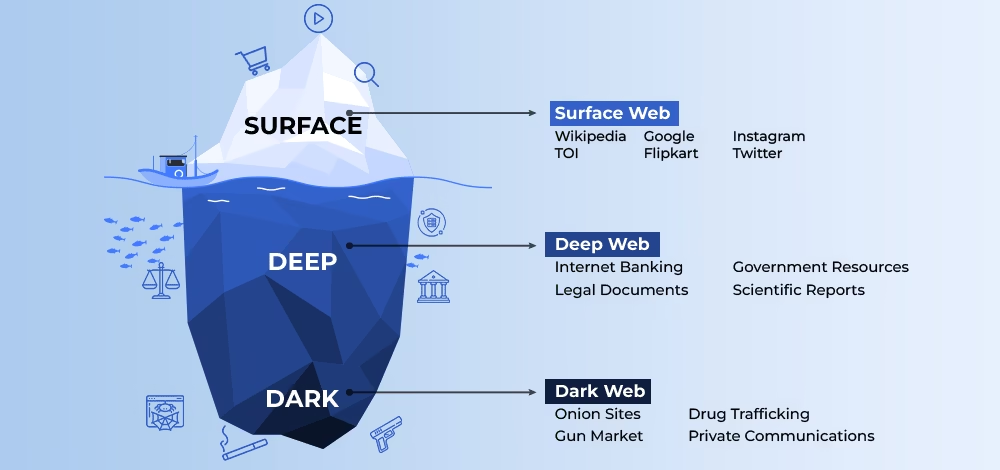

If the internet were an iceberg, only a sliver would be visible above the waterline. That visible tip—the websites you reach through Google, YouTube, or Instagram—is just 4 to 10 percent of the whole. The rest lies beneath: unreachable by conventional search, hidden not by malice, but by design. Yet this hidden mass is overwhelmingly mundane. Contrary to viral myths, it contains billing portals, email inboxes, and academic journals—not digital underworlds.

Understanding the internet’s true structure begins with separating fact from fiction. There are not seven secret layers. There are three functional categories: the surface web, the deep web, and the dark web. Only one is designed for anonymity. None resemble the hierarchical descent into darkness portrayed in online lore.

The Surface Web: What Search Engines See

The surface web is the internet most people know. It includes every page indexed by search engines—news articles, e-commerce sites, public blogs, and social media profiles. These pages use standard protocols (HTTP/HTTPS), require no special software, and are accessible to anyone with a browser.

What makes content “surface” isn’t its popularity but its indexability. Search engines deploy automated bots (crawlers) that follow links and catalog pages. If a site allows crawling and lacks login barriers, it joins the surface web.

This layer is vast in human terms—billions of pages—but tiny in data volume. A 2020 study by the University of California estimated that the surface web accounts for less than 5 percent of total online content by size. The rest? Locked behind doors.

The Deep Web: The Internet’s Invisible Bulk

The deep web isn’t secret—it’s just private. It includes any content not indexed by search engines, typically because it requires authentication or resides behind query-based interfaces. Examples include:

- Your Gmail inbox

- Online banking dashboards

- University library databases (e.g., JSTOR, IEEE Xplore)

- Government records behind login portals

- Corporate intranets and internal HR systems

Crucially, accessing the deep web requires no special tools—just a username, password, or authorized query. A doctor pulling up a patient’s file or a student downloading a research paper is navigating the deep web. It’s not illicit; it’s routine.

Estimates vary, but cybersecurity researchers consistently place the deep web at 90 to 95 percent of all online data. The vast majority is harmless, regulated, and essential to modern life. As data privacy laws (like GDPR and CCPA) expand, more content moves into the deep web—not to hide, but to protect.

The Dark Web: A Sliver Within the Deep

The dark web is a tiny subset of the deep web, distinguished by one key feature: it requires specialized software to access. The most common is Tor (The Onion Router), which anonymizes traffic by routing it through volunteer-run nodes worldwide. Others include I2P and Freenet.

Unlike the broader deep web, dark web services (called “hidden services”) use non-standard domain suffixes like .onion and are not accessible via regular browsers. This design prioritizes privacy—not secrecy. Legitimate uses exist:

- Journalists using SecureDrop to receive anonymous tips

- Activists in authoritarian regimes bypassing censorship

- Privacy-conscious users avoiding commercial tracking

But anonymity also attracts illicit activity. Some dark web marketplaces have sold drugs, stolen credentials, or counterfeit documents. However, these are neither dominant nor unmonitored. Law enforcement agencies (like the FBI and Europol) routinely infiltrate and dismantle such platforms. A 2022 report by Recorded Future found that over 60 percent of dark web sites are inactive or scams, and high-profile markets (e.g., Silk Road, AlphaBay) have been shut down for years.

Critically, the dark web is extremely small. A 2023 study by Carnegie Mellon estimated fewer than 100,000 active .onion sites—a fraction of the 1.8 billion surface websites. Its reputation far outstrips its scale.

Debunking the Hierarchy Myth

Popular “internet iceberg” charts often place the dark web at “Level 5” or “Level 7,” implying a descent into increasing danger. This is misleading. The surface, deep, and dark webs are not vertical layers but overlapping categories defined by access method:

- Surface: public + indexed

- Deep: private + non-indexed (mostly benign)

- Dark: private + anonymized access (small, mixed-use)

There is no “deeper” level beyond the dark web. Claims about “Level 7” content—featuring live criminal streams or secret forums—are unsubstantiated. Cybersecurity experts and law enforcement agencies consistently state that such content, if it exists at all, is vanishingly rare and often hoaxes designed to harvest clicks or credentials.

Why the Confusion Persists

The myth thrives because it’s narratively compelling. Online forums, YouTube documentaries, and social media posts amplify worst-case scenarios while ignoring context. A student researching for shortleap.org might stumble upon an infographic claiming “90% of the internet is hidden and dangerous”—a claim that is both technically wrong and dangerously misleading.

In reality, most cybercrime happens on the surface web—phishing emails, ransomware scams, fake shopping sites. The dark web is a tool, not a territory. Like a locked room, it can be used for shelter or secrecy, but its existence doesn’t make the building inherently sinister.

Conclusion

The internet is not a labyrinth of secret levels. It is a layered system of access controls, privacy measures, and technical protocols. The surface web is what we share openly. The deep web is what we protect. The dark web is what we shield with encryption—sometimes for freedom, sometimes for harm.

Understanding this triad dispels fear and sharpens digital literacy. The next article will dissect the origins of the “7-level internet” myth, tracing how a technical metaphor warped into digital folklore—and why experts urge skepticism.